More Than Meets the Eye

More Than Meets the Eye

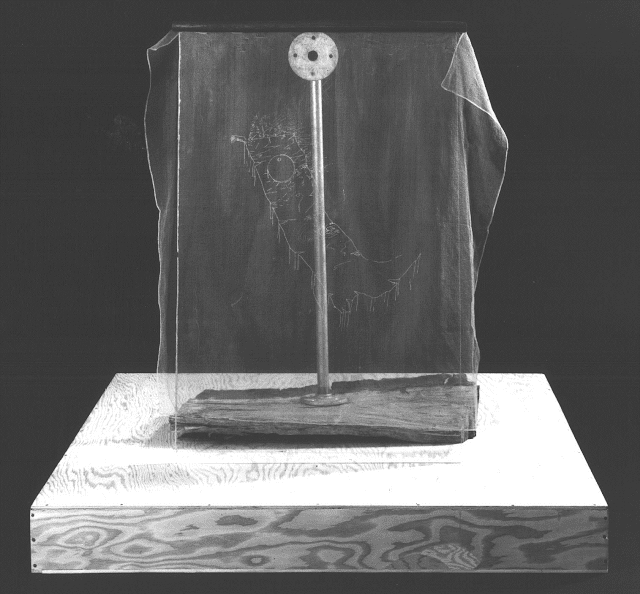

William T. Wiley and the Busted

Plexi "Eye Talisman

Strain," 1971.

A

museum is a repository, a time capsule if you will that is added to

periodically. What it means in the long

term is that something one has created is preserved for posterity and will

hopefully be shared with and seen by future generations. And while an artist created the work, it

requires someone with a well trained “Eye” to select the work for inclusion in

this open ended time capsule.

It

is one thing for a museum to add the work of an established, “consecrated,”

artist to its collection and another to see the value in a young, living,

artists’ offerings. It is validating

for a living artist to have one’s Art in a museum’s collection.

Ellen

Johnson, who taught modern art history at Oberlin College, was a great friend

to many artists. She also possessed a

discerning eye. She surely suggested to

her friend, Ruth Roush, that the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College

should acquire a piece by William T. Wiley.

Wiley, a 35-year-old California artist, was a key figure in what was

loosely referred to as West Coast Funk.

West

Coast Funk was more or less a Duchampian influenced attitude against

the

self seriousness of “High Art.”

"Eye

Talisman Strain" was accessioned, as a Gift from Ruth C. Roush, about the

time I came to work for the museum, in 1972.

Wiley’s piece was a free standing sculpture/assemblage, composed of a split log, sitting on an unpainted plywood base, a 3/4 inch diameter piece of cast iron pipe screwed to the log with a standard fitting and an elbow joint at the top, heading forward a few inches to act as support for a roughly 18" X 28" sheet of 3/16 inch thick, jagged, sheet of plexiglas. The plexi tilted back at a slight angle and was held erect by the pipe armature. There were no screws or other types of fasteners to hold the plexi in place, just the effect of gravity. A transparent, gauze-like square fabric covered most of the face of the plexiglas. A hunk of green garden hose, slit lengthwise, clamped the veil to the plexiglas along the top edge.

The primary element in this whimsical assemblage was the image engraved on the plastic. Wiley had scratched the image of an old boot and other seemingly random marks onto an otherwise worthless scrap of plastic. The plastic was the cheap type commonly used as window replacement, most often found in storm doors. It is likely that Wiley retrieved this particular piece of plexiglas from a trash bin. The concept of making ART from humble materials would have been a cornerstone element for a piece comprising such clearly worthless objects as: a log, a snagged scarf, a hunk of rubber hose, an old piece of iron pipe, and a broken window. It was obvious that he had found the original sheet of plexi in some sort of distress and contributed to the general dilapidated look with his engraving, which was likely done with an ice pick or similar hand tool. He had not used engraving tools nor anything designed for that purpose. Wiley is known to have made a number of prints using plastic plates as the matrix, rather than the traditional copper plate. If the boot had been inked and printed as an engraving, which it had not, it would have been a fair representation of a map of Italy, complete with indentations in the coastline. As it was, the toe of the boot was pointing in the “wrong” direction, or backwards, for the engraving to have been a proper representation of a map of Italy. Approximately where Florence would be located if this was a map, lies a circular shape with a smaller, off center circle inside. This circle within a circle is an illusion of a ball with a highlight. It is not a target, but can serve as a focal point. Does this circle indicate a geographical location of significance? Is Wiley pointing to Florence, rather than Rome, to make one of his ironic comments? Not necessarily. It is most likely a device left to contradict the illusion to the map, reminding us that this is not a map. Neither is the image truly a map nor a boot. The boot is rendered with lines that put it into perspective as a slab shape and not an object capable of having a human foot inserted into it. As in Wiley’s typical drawing style, the illusion is not photographic, but a “doodle” drawing of a rustic, dog eared, wooden sign like shape.

The

same basic format, as in “Portrait of Radon” is present in a 1972 lithograph,

“Thank You Hide”. This print was made a

short time after “Eye Talisman Strain”, and has a few geographic references,

most notably the word “Chicago”, in red

cursive. “Thank You Hide” was printed on an actual map shaped piece of

leather, alluding to the types of charts that the explorers would have possibly

used. This time he has positioned a

black disk over the approximate location of the city of Chicago, as well as

including the cursive script.

We

know the significance this time; since the lithograph was printed at Landfall

Press, located in Chicago. It was

Wiley’s way of sharing his appreciation for the support he received from

Landfall Press. So, perhaps Florence does

have significance, after all.

Still,

“Eye Talisman Strain” and its execution brought several other associations to

mind. I immediately recalled John Cage’s

story of a visit by Isamu Noguchi. Cage

includes the story in his 1965 performance; “How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and

Run”. I possess a recording of Cage’s

deadpan style delivery of the entire performance and can conjure up the

monotone reading of the following:

One

evening when I was still living at Grand Street and Monroe, Isamu Noguchi came

to visit me. There was nothing in the

room (no furniture, no paintings). The

floor was covered, wall to wall, with cocoa matting. The windows had no curtains, no drapes. Isamu Noguchi said, “An old shoe would look

beautiful in this room.”

John

Cage’s description of his room sounds more like an art gallery than living

quarters. Wiley’s “Eye Talisman Strain”

had but one recognizable representational feature, the boot, as it sat on the

floor of a sparse contemporary art gallery. In a way, Wiley’s shoe/boot, put

into an actual gallery, acts as a low tech holographic or laser projection of

Naguchi’s suggestion. Wiley crystalized

the words and gave them form, in two dimensions. Wiley’s piece sat somewhat close to the wall, which allowed the

viewer to catch the boot image against the white gallery wall.

Because

the piece sat so low to the floor it required one to lean over to read the

engraved image of the boot. If one

leaned over long enough, a back strain might be expected. If one tried to focus on the lines scratched

into the clear plastic to make out the subtle image, eye strain could result. Wiley plays word games, following in Marcel

Duchamp’s footsteps. Duchamp took a

multi-pane French window and titled it “Fresh Widow”. Wiley also frequently gives a title based

upon a miss heard or miss pronounced word.

In naming “Eye Talisman Strain”, Wiley has obviously split the medical

condition, eye strain, with

the

insertion of the word: talisman. A

talisman is defined as anything whose presence exercises a remarkable or

powerful influence on human feelings or actions. Hmmm, perhaps designed to hurt ones eyes?

The

“Leaning” plexi and reliance upon gravity rather than adhesives or an armature

to keep the object in an erect position, remind me of Richard Serra. That the lightweight materials in “Eye

Talisman Strain” did stand without fixed support added to the intrigue of the

piece. Whether or not Wiley consciously

intended a nod to Serra, this artwork was created in a time period when Serra’s

impact was unavoidable. “Eye Talisman

Strain” seemed a “Propped” piece, on a more folksy level though, but still akin

to one of Serra’s early, more aggressive pieces.

While

Wiley’s piece may have provided homage to other artists, it was gentle and

playful. It was not aggressive and

definitely not a slap in the face or confrontation to anyone. It sat on the floor in real time and space. Gravity held it in place. Otherwise, the lightness of the piece might

have caused it to float away.

Yet,

despite the light spirit of the piece, it was such a departure from traditional

sculptural forms and materials that uninitiated visitors and our own museum

guards may have found it difficult to connect with “Eye Talisman Strain”.

Our

museum was so compact and visitors so infrequent that the guards usually sat at

a tiny desk in a corner of the sculpture court with little to do except read or

do needlepoint. From this corner vantage

point anyone could be seen entering the galleries. The floor was such that all foot steps were

audible. The guards watched over the

museum’s exhibited artworks, including the inoffensive Wiley, in a museum so

quiet you could hear a pin drop, a page turn, or an embroidery needle pass

through a piece of cloth.

One

day, while measuring some prints for matting, I heard a commotion outside my

workroom. The door was open and I could

tell the activity was unusual. I stood

up and as I left the room, our most

elderly museum guard came hobbling around the corner. This old guard, while spry for his age, did

suffer from arthritis. I had never

imagined him moving so fast before. From

his expression it was clear he was upset, squeaking between gulps of air that a

vandal had just destroyed “That piece of plastic sitting on the log!” For this octogenarian, the event became the

crime of the decade. He had been roused

from his embroidery hoop by a sudden crash and the sight of a father and his

five-year-old son fleeing the building.

Caught between the embarrassment of allowing something under his watch

to be broken and the excitement of thinking he’d “witnessed” a crime of

vandalism. He wasted no time coming to

find me. In a flash I was in the gallery

and surveyed the crime scene.

Unfortunately

the Wiley was broken. The act may have

been vandalism but the greater likelihood was that the little boy had been

curious about Wiley’s object and touched the plexiglas from behind to see if

something was holding it against the piece of pipe. I’m certain the consequence surprised

him. The plexiglas had fallen forward so

that the top, with the rubber hose, rested on the floor, furthest from the

plywood base. The bottom edge of the plexi had stayed up on the base, making

the sheet of plastic seem like a clear ramp from the floor to the

sculpture. Unfortunately this illusion

would only have been seen by the little boy, and lasted only a small fraction

of a second, as the pipe toppled forward.

The full weight of the falling pipe acted as a mallet or axe, severing

the sheet of plastic at the edge of the plinth.

Plexiglas, compared to standard glass is reasonably durable

glazing

material. It requires some effort to

break it and it doesn’t tend to shatter.

This was a clean break, on the diagonal defined by the edge of the

base.

I

called the museum photographer so he could document the aftermath, then removed

the damaged piece from the gallery. At

that time the Intermuseum Conservation Association was housed in our building.

The ICA was an art conservation training facility created by the late Richard

Buck and was where many of the art conservators in the United States learned

their trade. The conservators took one look at the breakage and shook their

heads. The Wiley had become a Humpty Dumpty.

To

add insult to injury, the museum’s insurance deductible was far greater than

the value of the artwork at the time.

Only Wiley could repair the piece and the museum’s insurer wasn’t going

to provide compensation.

Wiley

was contacted and apprized of the dilemma. He graciously agreed to do what he

could to repair or replace the broken component. I was instructed to pack and

ship the broken plexi to him. Years of

carefully packing artworks so they would arrive at their destinations in good

condition, seemed quite beside the point.

Still, I treated the broken plexi with the same attention so it wouldn’t

get any worse on its trip to Wiley. Burlington Air Freight picked up the crate

and notified me of delivery. After that

I put the piece on the back burner of my mind.

Wiley

could have glued the plastic back together, put it between two pieces of plexi

(a la Duchamp’s Great Glass), or made a copy/replica of the original. Instead he bought a fresh new sheet of plexi

and made an entirely new engraving, nothing like the old boot.

He

had taken the opportunity to update his imagery and reincarnate the piece with

new life. He further illustrated his

correspondences with me concerning the disposition of “Eye Talisman Strain”,

which act as documentation for the artwork and testify to Wiley’s appreciation

that Oberlin, through Ellen Johnson’s efforts, purchased the original piece.

However,“Eye

Talisman Strain” , to my knowledge, has been in storage since its rebirth.

A

museum is a repository, a time capsule if you will that is added to

periodically. It is validating to have

ones Art in a museum’s collection. What

it means is something one has created is preserved for posterity and will

hopefully be shared with and seen by future generations. And while the artist creates the work, it

requires someone with a well trained “Eye” to select the work for inclusion in

this open ended time capsule.

It

also takes the best possible care by the staff of the museum to preserve an

object and a future discerning “Eye” to keep the artwork seen. It is through this perpetual movement from

eye to eye that artworks and culture remain vital.

Sandy

Kinnee

January

2002

Comments

Post a Comment