An Invisible Dancer and a Charcoal Boat

Back in the 1960s Ann Arbor was an incubator of performance Art, with my friend and mentor Milton Cohen as one of the pivotal leaders of the Once group. Milton brought visual arts into the temporal world already occupied by music, dance, and theatre. He was at home with composers, poets, actors, musicians, dancers; the world of here, then gone.

Cohen, who was hired by the University of Michigan Art Department as a painter, evolved into a painter whose medium became light, color, and motion. In his studio, known as the Space Theater, above East Liberty Street, he scheduled performances of his colored light, sound, film, projections, optical manipulations, and a live dancer for a small audience who sat on cushions on the floor.

I attended several performances over the years. The events were free of charge. Famously, during the early 60s Milton arranged for an entire crew along with all his Space Theater components to perform at the Venice Biennale and subsequent tour of additional European cities. With all of the Space Theater elements in motion simultaneously, one might expect there was quite a bit of randomness and happenstance. This was to be an ticipated, yet the performance was composed and scored as one would a complex play or multifaceted event. Milton gifted me with two unique performance scores and a negative blank score, illustrated here. Clearly, the scores demonstrate that his Space Theater was calculated and not random or improvised.

Steve McMath and I attended one of the ONCE concerts in Ann Arbor, in which Cohen played no part. It was a presentation of “She Was a Visitor”, by the composer Robert Ashley. During the performance an audience member accidentally knocked over an empty Coke bottle and it meandered beneath the seats, rolling down the inclined floor all the way to the stage, greatly augmenting the musical experience. Steve and I smiled at such a brilliant and random contribution to the event. John Cage, who had previously been involved with the Once group, would have adored the impromptu performance of the wayward bottle. This is not to say that Ashley either appreciated or was horrified by the unexpected sound of the rolling glass bottle. It just was a delight to the audience, something very “Sixties”.

Returning to my connection with Milton, it was crazily unique. He was unaware, as was I, of the threads, or at least one particular link between us: the first art history teacher I had two years before at the Junior College. It was a matter of bizarre chance.

It happened that Milton needed a dancer for his upcoming Venice performances. He found one, a student at the university working on her degree. She was married, but that did not stop them from beginning a relationship. He whisked her off to Venice. They had a daughter. I think they married, but if they did it would only have been after the dancer divorced my first Art History professor. Anyone who knew the elderly art historian thought he was gay, perhaps he was only, to use his own term: “a Sissy”. He was heartbroken. When he heard I was transferring to Ann Arbor he let it drop that his former-wife, a dancer, had run off with a professor at U of M. I never met or saw her. Never saw Milton’s daughter.

Milton’s daughter, however, is, I believe, how I came to own one of his early drawings. I suspect, after his death, she consigned his early paintings and drawings to a gallery that specializes in mid-century artworks. When he was hired at Michigan Milton's portfolio demonstrated his ability to create both representational drawings and abstract paintings. It was decades after his passing that I discovered and purchased one of his charcoal drawings of a ship from the purveyor of “mid-century artworks”. Physical evidence of Milton’s artistry is sparse, to say the least.

Now, I have come to the part where I explain why Milton Cohen made temporal rather than concrete art. From an early age he was interested in “advanced Art”. He studied with the most modern artists at the time. During the war he served in Italy. He saw Art and saw smashed art.

He saw that making more art only made more objects and the world was overflowing with useless objects. Cohen made a particular point in his Light & Motion classes to speak of the over-proliferation of physical artworks in the world. He pointed out that art museums only display a tiny percentage of the artworks they hold in their collections. He truly felt the world did not need any more physical artworks. As the world was overpopulated by human beings, so was it flooded with the products that humans made.

Milton Cohen switched over to temporal creations. He did visual performances, creating events that flickered and were gone. He left no footprints or trash in his wake. He stopped making objects.

Only lights and motion, only sounds and reflections, only whispers and shadows.

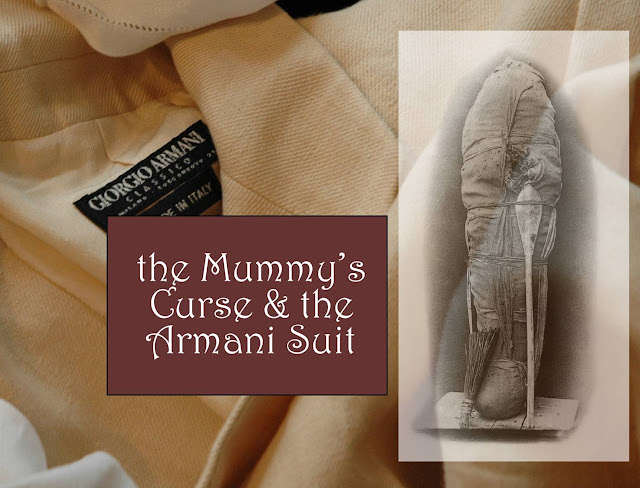

Before I left Ann Arbor, Milton gifted me three scores for his Space Theater performances, illustrated here. That charcoal drawing of the ship is shown last. It is in a drawer in my studio, under a stack of my own too numerous works on paper.

Milton Cohen once made objects: one more drawing than humans need to view as well as three physical artifacts of a temporal event.

More concerning Milton Cohen's studio class in AnnArbor:

Milton's Gray Wall

I am not certain where this would be filed, under painting or under obscuring. During my senior year at Michigan I took a final course from my mentor, Milton Cohen. Milton’s Art could not be hung on a wall. It might better be described as projected on a wall, then gone. Anyone who took his classes understood there would be no art materials involved, no paint, no canvas, no paper. Milton believed that as the world was becoming over-populated, it was also being swamped by the things that humans create, things being used and pitched out. He went so far as to state that there is already more art than is necessary. He was for an Art that is here and then gone, an art that does not add to the already overflowing trash heaps of civilization. He was for an Art that catches people off guard, then melts away. Milton was no longer a painter. He would have suggested his students plant a real tree rather than waste paint on a two-dimensional happy tree.

The course was called Light and Motion, yet never stayed the same. I had already taken a couple semesters from Milton, so knew to not expect anything or rather to not try to anticipate anything. It was perhaps during this particular group assignment where I got the notion that being a student in a contemporary artmaking class was more about following directions of the professor and later trying to figure out what the lesson was about. The value in the task was not in the task. It was also not one of those silly assignments meant to be “spontaneous” or “faux-creative”. There was always some unrevealed, often subtle lesson to be discovered. Or there wasn’t.

This particular class assignment was a communal project. Each member of the class was to do the same thing. There was no deviation, no individual “expression”, nothing personal. Each student contributed to the project in the same way as each other class member. There were no leaders, no followers. No one had an inkling of what was going on except at the moment.

Gigantic stacks of plywood disks appeared in the studio, each disk the same diameter as all others. Cans of oil-based enamel paint and brushes were evenly distributed amongst the students. One side of each disk was to be painted gray. Enamel dries slowly. The next day, after the gray was dried the other side would be painted red or blue or yellow or black or white or gray.

When both sides were completely dry a small hole was drilled in the center of each disk. Each of us had painted both sides of thirty-six circles. Two days of non-creating were filled more with the breathing of paint fumes than anything else. When the last student had painted the last disk every student wondered how there could possibly be any value to such a task? This was little more than busy work. Having had experienced two previous courses, I said nothing. There was nothing to say. I certainly had no idea where this was going. I had learned, as I said, to not anticipate. As the second side of the disks dried the windows were opened and Milton took the entire class down the street on a mass coffee break.

As we walked to the coffee house, not a single student commented on nor seemed to notice that we had passed a construction screen, a six-foot-high temporary plywood wall. The wall masked activity behind it from public view. Work was in progress. Yes, it was a real construction site and those interested knew some new building would appear behind the wall, but for the time being a blank barrier kept people out. There was nothing to see until it was ready to be seen. The wall was painted gray. We drank our coffee and nibbled cherry donuts. Nothing was said about that wall. At the coffee shop Milton gave a short lecture about Magic Squares. Our overnight assignment was to construct a magical, numerical square, six by six. In a magic square all rows and columns add up to the same sum. As no one mentioned the blank wall, nothing was said about it.

The following day all were given thirty-six long screws, a screwdriver, and thirty-six short metal tubes. Nothing creative had happened in the classes and nothing would. Nothing to express ourselves was about to take place. We were simply about to execute a communal work project, one that had no message, no point and one in which no one had any investment. You have already correctly assumed it had something to do with the long gray plywood wall. The class spread out evenly along the wall. Using a carpenter’s snapline each student was given a six-by-six grid at the intersection of the lines the student would poke the long screw through the disk’s central hole, slide the metal tube, like a washer, on the screw and fasten the disk/screw/tube unit by screwing it into the gray plywood wall. Each student would arrange the disks with the gray side out and the colored side in the same order as they had arranged the numbers of their magic square. Red, yellow, blue, black, white, gray would face the wall.

The completed wall, on a normal cloudy and overcast Michigan day, looked like nothing. The gray disks on gray were nearly invisible. One could walk right past without noticing the disks. The effect on such a day was underwhelming.

Under different conditions different things might be noticed by anyone with eyeballs wishing to see magic.

For instance, as the sun crossed the sky the disks would cast shadows, not unlike so many sundials in transit. Then, as the sun reached a certain point sunlight would bounce off the gray wall and the red, yellow, blue, black, gray, and white backsides would cause the dull gray wall to shimmer in a pattern of otherwise hidden magical squares………….where all rows and all columns add up.

As is often said, there is nothing to see until you see it.

Postscript- to my knowledge the way the colors glowed was too subtle to be photographed, so no pictures memorialize the wall. The wall was only up for so long as it was needed. Not being an artwork, disks one by one vanished, perhaps to be tossed like unsatisfactory and free Frisbees. Eventually, the entire wall was dismantled and became landfill with no regrets. With or without the quietly magic disks it was going to be landfill.

Comments

Post a Comment