Brown Paper Grocery Bag Drawings

Brown Paper Grocery Bag Drawings

I was four or five years old and knew

This boy and that girl only from afar

Sounds from their moving lips

Not words just strange noises

They looked like drawings of people

Made with a yellow pencil

On a brown paper bag, then erased

Not a new yellow pencil

On the first day of school

But the kind of pencil that someone

Chews and bites, a stubby pencil

With a hard nub of a pink eraser

I did not play with these children

They did not play with me

Their mothers looked at the dirt

Their mothers were also erased

Drawings on brown grocery bags

No one spoke of these wraiths

Beings that came one week

And vanished the next

Hauntingly invisible

Five Birthday Candles and a Gauze Fuse

Having been born after World War II, what would I, as a small child know of massive scale human displacement? How was my little brain to deal with the idea that most men I saw had two legs and my neighbor only one. I took it as matter of fact that some people had fewer legs, or hands or fingers. These people had gone away and came back as they came back. I did not know what was involved in the loss of a limb or eye or life. To a four year old it was not a wonderment or misfortune. It just was. Only years later did I understand that the man next door had his leg blown off in Italy.

I also, was so young and innocent and protected that I did not have an inkling who those children were who stood silently on piles of dirt, frozen, hands at their sides, posing for cameras that weren’t there. When I saw them I could not understood how they could not speak or understand, they made sounds that meant nothing. These children were like ghosts of boys and girls, all gray and brown, faint like ashes and dust. After a moment they would flee. Maybe I was seeing ghost beings. I did not know, could not understand. Nobody said anything.

The one-legged neighbor never said anything about his missing leg. No one said a word about the silent kids who were there one moment and then gone. I knew nothing of war and refugees. I was turning five soon.

After you turn five you could go to school where there would be many boys and girls to play with, or so I was told. When you turn five you can have a birthday party. You can play games, open birthday presents, blow out candles and be the center of attention. I liked being the center of attention.

As my birthday approached my mother and I walked the quarter mile or so to the little grocery store to purchase things for my party. There were rolls of colorful crepe streamers, noise makers, paper hats, potato chips, orange pop, Neapolitan ice cream (the pink, white, and chocolate kind), oh and candles. There were other things, too much to carry home. The little store would deliver these to our home, which my mother appreciated.

I should tell you about this little grocery store. This I did not know at age four or five. The tiny store was the nearest shop for many miles. The building had been in this location for a longer time than I could have known. The sign over the door read: HENSCHEL’S GROCERIES. It was a general store, selling a little of everything. The family, as I learned was relocated. They lived over the store and had one child. The parents spoke broken English. The son, too young for school, spoke only what the parents spoke at home. When the groceries were delivered to our little home, the little boy accompanied the father. My mother, noticing the boy, asked if he could come to my birthday party.

My birthday party was quite small, possibly there were two girls, whose names I do not remember and three boys. The Henschel boy showed up at my birthday party with his hair greased. He wore a heavy gray wool suit and a bright blue bow tie. The tie was not the type usually seen. This tie was skinnier and more like a ribbon on a gift. The quiet boy’s fingers were artificially pink, like Pepto Bismol. The palms of his hands were bandaged with gauze. This child-stranger who said nothing, was probably introduced by name. It was immediately forgotten or as a child I did not understand it was a name. While the others sang Happy Birthday, the Henschel child moved his lips and bobbed his head, as if singing. He said nothing, but ate the birthday cake and the pink, white, and brown ice cream. I know it was a nice thing that my mother did, but her good intentions made little sense. The boy was a total stranger and did not understand, or at least was unable to participate when we played musical chairs or pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey. The party continued well into the night, and everyone passed out. No, that is not true. The party concluded shortly after the opening of the gifts and the ice cream was gone and the orange pop ran out.

The neighborhood children walked home for dinner with no appetite. They just lived a few doors away. The Henschel boy’s mother or father would come fetch him.

My mother asked me to assist her by cleaning up. She had already taken a load of paper plates, wrapping paper, and other burnable waste to the trash fire behind the house. Back in those days people burned their own refuse. There was a small blaze in the fire pit. The Henschel boy had not been picked by his parents, but left our home when the other children departed. had his back to me. He was in our backyard, standing over the flames, his wool jacket on the ground. He had also removed his tie and dress shirt, discarded next to his jacket.

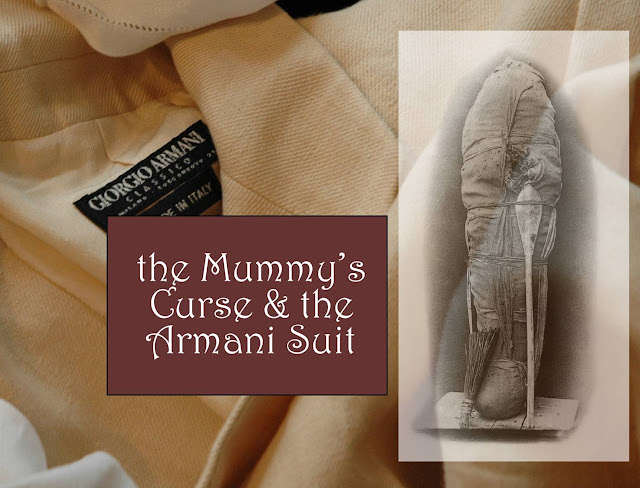

Previously, I had only noticed the pink on his hand and the white gauze. I now saw what his jacket and shirt had been covering. His arms and torso were painted in Calamine lotion, wrapped in gauze bandage, like a pinkish Egyptian Mummy. He stood over the fire and dangled a loose end of the gauze, fascinated as the flames climbed.

I screamed and ran to get my mother.

Comments

Post a Comment